Git Tutorial: Branching

| Tutorial | |

|---|---|

| Title: | Git Tutorials |

| Provider: | HPC.NRW

|

| Contact: | tutorials@hpc.nrw |

| Type: | Online |

| Topic Area: | Revision control |

| License: | CC-BY-SA |

| Syllabus

| |

| 1. Basic Git overview | |

| 2. Creating and Changing Repositories | |

| 3. Branching | |

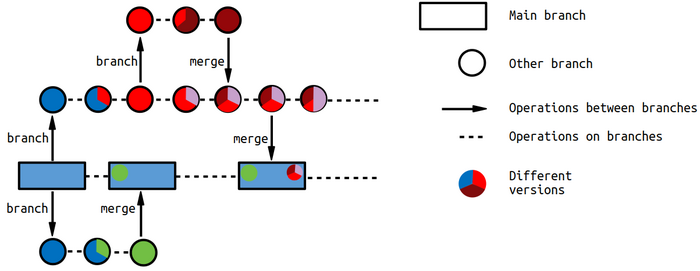

Branching is an important feature of Git, which enables simultaneous work on different parts of a code with minimal interference between acting parties. As the name implies, branching refers to the creation of a separate line of repository tracking that branches of from your "main" repository (also called a branch, but can be understood as the trunk). When developing new features you do not necessarily want to directly commit your changes to "main", because they might interfere with your colleagues contribution of other features on a different branch. Even when differences do not directly interfere, they can still lead to a more cumbersome merge of both branches into "main", once all changes are complete. In larger projects this merge ing into the "main" branch is often blocked for most users. A so-called pull request must be made, so that a responsible person can pull your changes from your branch and merge them into "main".

To view all existing branches use the git branch --list command:

1user@HPC.NRW:~$ git branch --list

2* main

We can see that currently the project contains only one branch called "main" (line 2). The "*" next to it is used to mark our current branch. Before we continue with the tutorial, a look at Figure 1 might be helpful. It visualizes the basic idea behind branching within a repository. Moreover, we can see the similarities between the relation of other branches to the main branch and the relation of a local repository to the remote repository.

Handling Branches

Creating a new branch is as easy as entering git branch <name of branch>:

1user@HPC.NRW:~$ git branch branchingTut

2user@HPC.NRW:~$ git branch --list

3 branchingTut

4* main

5user@HPC.NRW:~$ git branch -a

6 branchingTut

7* main

8 remotes/origin/main

In above example we can see that creating a new branch does not imply switching to it (the "*" is still next to "main"). Further, displaying all local and remote branches through git branch -a, we see that the new branch does only exist locally and not in the remote repository unlike "main" (line 8). The new branch will be identical to the last commit of the current branch, in our case "main".

To switch to a different branch we use git checkout <name of branch>:

1user@HPC.NRW:~$ git checkout branchingTut

2M someFile

3Switched to branch 'branchingTut'

4user@HPC.NRW:~$ git branch -a

5* branchingTut

6 main

7 remotes/origin/main

Line 2 informs us about a Modified file named "someFile". This can happen if we make changes to our repository (like Adding or Modifying files), but do not commit them before switching the branch. Naturally, this also happens when we want to switch to a branch with different contents than in hour current branch.

Keep in mind that a git checkout <name of branch> is not like a git clone operation and therefore does not make a full copy of a different code branch. Instead, it tracks the commit history of the chosen branch and reproduces the changes in your repository. Any modifications you commit now will be added to that branch.

If we want to create a new branch and directly switch to it, we use git checkout -b <name of new branch>.

|

Usually, a branch is created from the most recent commit of the branch you are currently on. If we want to create it from a different branch (and switch to it), we will have to use git checkout -b <name of new branch> <name of different branch>.

|

To delete a branch we type git branch -d <name of branch>. However, this will not be possible if the branch contains uncommitted changes. We either have to perform a commit first or use the option -D instead of -d.

|

Deleting a branch as shown above only deletes its local version. A remote branch has to be deleted this way: git push <name of remote repository> --delete <name of remote branch>

|

Renaming our current branch is done through the command git branch -m <new name of branch>.

|

Remote Branches

If others are supposed to have access to our branch (or we want to have access from different locations), we need to make sure that it also exists in the remote repository by entering git push <name of remote repository> <name of branch>:

1user@HPC.NRW:~$ git push origin branchingTut

2Username for 'https://github.com': HPC.NRW-User

3Password for 'https://HPC.NRW-User@github.com': ********

4#Enumerating objects: 15, done.

5Counting objects: 100% (15/15), done.

6Delta compression using up to 12 threads

7Compressing objects: 100% (13/13), done.

8Writing objects: 100% (13/13), 42.00 KiB | 10.50 MiB/s, done.

9Total 13 (delta 6), reused 0 (delta 0)

10remote: Resolving deltas: 100% (6/6), completed with 1 local object.

11remote:

12remote: Create a pull request for 'branchingTut' on GitHub by visiting:

13remote: https://github.com/HPC.NRW-User/Wikipages/pull/new/branchingTut

14remote:

15To https://github.com/HPC.NRW-User/Wikipages.git

16 * [new branch] branchingTut -> branchingTut

17

18user@HPC.NRW:~$ git branch -a

19* branchingTut

20 main

21 remotes/origin/branchingTut

22 remotes/origin/main

This is very similar to the previous push operations with the only difference being that instead of the "main" branch in the remote repository, we will be using the "branchingTut" branch. As this branch did not exist yet, it will be created for us. In lines 18 to 22 we can see all existing branches including the newly created remote branch.

A remote checkout works the same way a local checkout does. The main difference is that your local repository might not be up to date with remote branch information, which is why we might miss updates on existing branches (as well as respective git log data). Below, you can see Git output for a user who cloned our repository after the first tutorial, but before branching was introduced:

1otherUser@HPC.NRW:~$ git branch -a

2* main

3 remotes/origin/HEAD -> origin/main

4 remotes/origin/main

In order to see the newest changes in the remote repository, they need to use the fetch command:

1otherUser@HPC.NRW:~$ git fetch

2Username for 'https://github.com': HPC.NRW-otherUser

3Password for 'https://HPC.NRW-otherUser@github.com':

4remote: Enumerating objects: 15, done.

5remote: Counting objects: 100% (15/15), done.

6remote: Compressing objects: 100% (7/7), done.

7remote: Total 13 (delta 6), reused 13 (delta 6), pack-reused 0

8Unpacking objects: 100% (13/13), done.

9From https://github.com/HPC.NRW-User/Wikipages

10 * [new branch] branchingTut -> origin/branchingTut

11

12otherUser@HPC.NRW:~$ git branch -a

13* main

14 remotes/origin/HEAD -> origin/main

15 remotes/origin/branchingTut

16 remotes/origin/main

Line 10 informs them that a new branch exists in the remote repository. Lines 12 to 16 show that they can see the "branchingTut" branch, however, they still do not have a local version of it. Using git checkout <name of remote branch> they can then create a local branch based on the remote one.

It is possible to display updated remote repository information without actually updating:git ls-remote origin

|

git fetch <name of remote branch> can be used to only update information on one particular remote branch.

|

If more than one remote repository is available, git remote update will update information on all of them.

|

If we have several remote repositories, we need to further specify the desired branch: git checkout -b <name of branch> <name of remote repository>/<name of remote branch>

|

git checkout is actually more versatile and not only used for switching or restoring branches. Therefore, beginning with version 2.23, Git introduced git switch <name of existing branch> for switching to a different branch.

|

git switch -c <name of new branch> creates a new branch and switches to it.

|

git switch is still marked as experimental in the Git documentation, which is why we only mention it here.

|

Best Practices

- Always start a new branch when working on a new feature and merge your changes and additions into the main branch, once the work is finished.

- Common branches are: main, develop, feature, release, hotfix. Naturally, those branches can have branches as well, e.g., when multiple features are being developed at the same time. However, depending on your environment, completely different naming conventions can be sensible.

- Several strategies exist on the structured creation of branches and branching conventions. We cover them here.

Glossary

branch: Used for creating new branches and displaying branch information.fetch: Used to update information on remote repositories (and branches).

Useful Links

- Interactive GitHub course: Introduction and basic branch operations

- Paper on aspects of RSE: Section 3.2.3 contains information on different branching workflows and where they are employed.